Twitter Timeline

[custom-twitter-feeds]

Categories

- Calculators (1)

- Company Research (295)

- Capricorn Investment Group (51)

- FirstRand Namibia (53)

- Letshego Holdings Namibia (25)

- Mobile Telecommunications Limited (7)

- NamAsset (3)

- Namibia Breweries (45)

- Oryx Properties (58)

- Paratus Namibia Holdings (6)

- SBN Holdings Limited (17)

- Economic Research (659)

- BoN MPC Meetings (13)

- Budget (19)

- Building Plans (142)

- Inflation (142)

- Other (28)

- Outlook (17)

- Presentations (2)

- Private Sector Credit Extension (140)

- Tourism (7)

- Trade Statistics (4)

- Vehicle Sales (143)

- Media (25)

- Print Media (15)

- TV Interviews (9)

- Regular Research (1,796)

- Business Climate Monitor (75)

- IJG Daily (1,599)

- IJG Elephant Book (12)

- IJG Monthly (108)

- Team Commentary (250)

- Danie van Wyk (61)

- Dylan van Wyk (27)

- Eric van Zyl (16)

- Hugo van den Heever (1)

- Leon Maloney (11)

- Top of Mind (4)

- Zane Feris (12)

- Uncategorized (6)

- Valuation (4,465)

- Asset Performance (115)

- IJG All Bond Index (2,069)

- IJG Daily Valuation (1,797)

- Weekly Yield Curve (483)

Meta

Author Archives: IJGResearch

New Vehicle Sales – November 2019

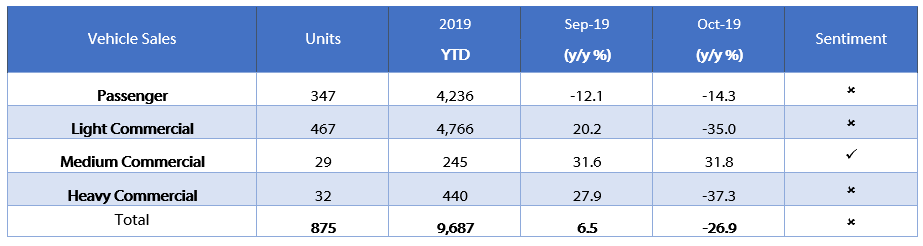

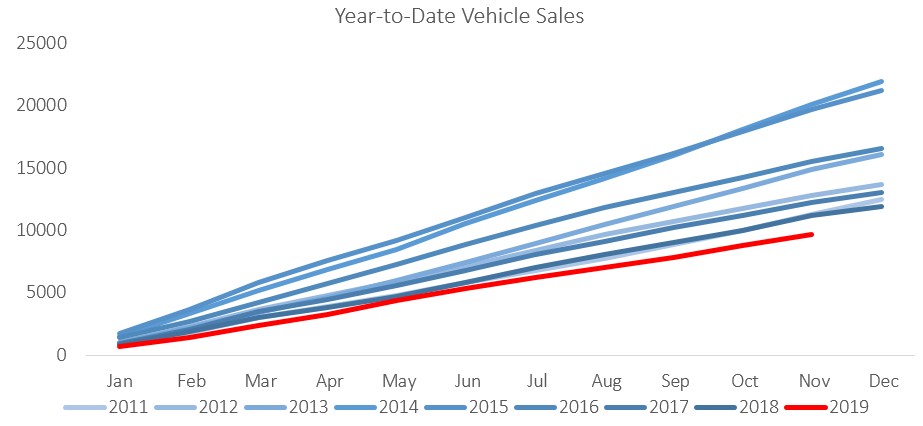

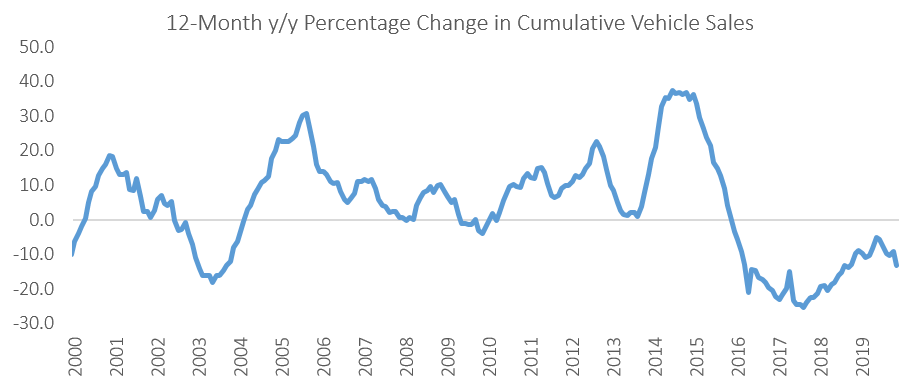

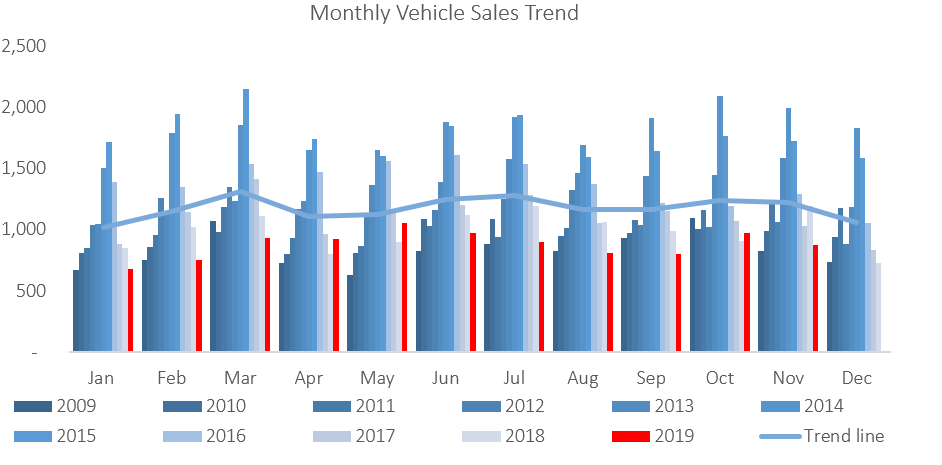

A total of 875 new vehicles were sold in November, a 9.9% m/m decrease from the 971 vehicles sold in October. Year-to-date 9,687 new vehicles have been sold, of which 4,236 were passenger vehicles, 4,766 were light commercial vehicles, and 685 were medium and heavy commercial vehicles. On a twelve-month cumulative basis, new vehicle sales continued its downward trend. 10,417 new vehicles were sold over the last twelve months, a 13.2% contraction from the previous twelve months.

347 new passenger vehicles were sold in November, contracting by 2.3 % m/m and 14.3% y/y. Year-to-date new passenger vehicle sales rose to 4,236 units, down 11.5% when compared to the year-to-date figure recorded in November 2018. Twelve-month cumulative passenger vehicle sales fell 11.8% y/y as the number of passenger vehicles sold continued to decline.

A total of 528 new commercial vehicles were sold in November, decreasing by 14.3% m/m and 33.3% y/y. Of the 528 new commercial vehicles sold in November, 467 were classified as light commercial vehicles, 29 as medium commercial vehicles and 32 as heavy or extra heavy commercial vehicles. 440 heavy vehicles were sold year-to-date, the highest sales figure for the period since November 2016. On a twelve-month cumulative basis light commercial vehicle sales dropped 16.6% y/y, while medium commercial vehicle sales and heavy commercial vehicles rose 6.2% y/y and 8.4% y/y, respectively. For the seventh consecutive month, there has been an increase in the sale of heavy commercial vehicles on a twelve-month cumulative year-on-year basis. The steady increase in this category indicates improved demand for durable goods by businesses.

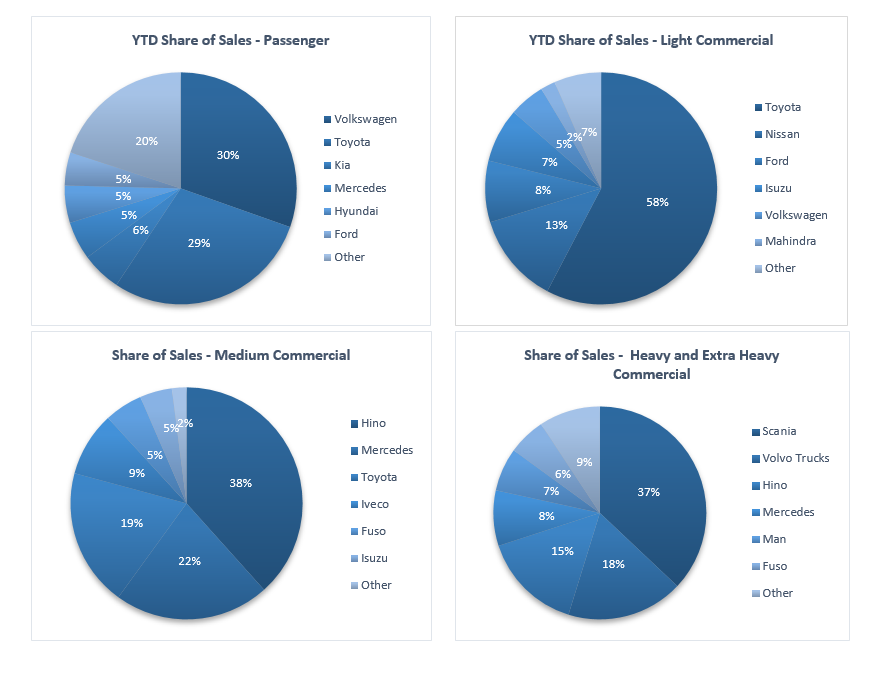

Volkswagen continues to lead the passenger vehicle sales segment with 30.4% of the segment sales year-to-date. Toyota remained in second place with 28.9% of the market-share as at the end of November. Kia, Mercedes, Hyundai and Ford each command around 5% of the market in the passenger vehicles segment, leaving the remaining 20.0% of the market to other brands.

Toyota retained a strong year-to-date market share of 57.7% in the light commercial vehicle segment and remains the market leader in the segment. Nissan remains in second position in the segment with 12.6% of the market, while Ford makes up third place with 8.6% of the year-to-date sales. Hino leads the medium commercial vehicle segment with 38.4% of sales year-to-date, while Scania was number one in the heavy- and extra-heavy commercial vehicle segment with 37.0% of the market share year-to-date.

The Bottom Line

Vehicle sales remain under pressure, with the year-to-date new vehicle sales in 2019 currently below 2010 levels, and the total new vehicle sales for the last 12 months down 13.2% from the same period in 2018. Both new commercial and new passenger vehicle sales are at their lowest year-to-date levels since 2009. However there has been an improvement in the demand for new medium and heavy commercial vehicles in 2019. This improvement has come off a very low base, but it suggests that the sectors of the economy that rely on these categories of vehicles may have turned the corner or bottomed out. However, we continue to expect business and consumer confidence to remain low and thus expect subdued demand for new vehicles going forward.